First Punic War—264-241 BC

Phase 2: Conflict at Sea, 260-256 BC

The Romans recognized that if they were to force the Carthaginians out of Sicily, they had to have sea power. So they set about building a war fleet of 120 ships; 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes. To build their quinqueremes, a Phoenician innovation, the Romans reverse engineered a captured Carthaginian war galley. While they were building their fleet, they had their rowers practice on dry land. As soon as their ships were built, they practiced on the water. After some more practical sailing along Italian coastal wars, they ordered a consular army south to affect a crossing to Sicily while the Roman fleet sailed south to provide support.

View of the island of Lipara

Lipara was the largest settlement on the island of Lipara, about 19 miles off the coast of Italy. The Roman attempt to take the island was a failure.

The first Roman sea engagement was an attempt to capture the city of Lipara by stealth. The consul Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio in command of 17 ships sailed into the harbor in order to take the place. The Carthaginians, stationed at Panormus, heard of this attempt and sent a squadron of 20 ships under the command of Boödes who trapped the Roman ships in the harbor. The Romans abandoned their ships and Scipio surrendered to the enemy.

Afterward, the Carthaginian commander, eager to see the Roman main fleet, came upon them sailing in good order. He lost most of his 50 ships but was able to escape with the remainder.

Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire (Classics) (Kindle Locations 998-1006). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

The Sea Battle of Mylae–260 BC

This is the first major sea battle off the north coast of Sicily in which a Roman fleet with a technical innovation (the Corvus, a platform with a hook at the end of it, that was dropped onto the deck of a Carthaginian vessel thus holding it fast and allowing heavily armed Roman marines to board the enemy ship and overwhelm its sailors) gave the Romans an advantage over the more experienced Carthaginians. The Roman fleet had 145 ships to 130 for the Carthaginians. The Carthaginian fleet lost 50 ships of its total number, a devastating defeat.

Land Campaign after the Siege of Acragas

Sicilian territory held by the Carthaginians, Romans and Syracusans–260-258 BC

After its victory at Mylae, the Roman fleet sailed westward to assist in the relief of Segesta by providing its marines as reinforcements. These soldiers also helped protect the city of Macella, further in the interior of the island.

The Romans also advanced along the northern coastal road toward Thermae, a city on the way to Panormus. There they were defeated by the Carthaginians under the command of the competent Hamilcar. Following up his success, Hamilcar made a counterthrust toward the center of the island and seized Enna. From there he ventured into Syracusan territory with the intent of persuading the Syracusans to switch sides.

Seesaw Land Campaign

Hamilcar once in Syracusan territory headed southeast and took the town of Camarina. Syracusa did not desert the Roman alliance. The following year, 258 BC, the Romans retook Camarina and Enna.

With renewed Carthaginian assertiveness in Sicily, the Romans realized that winning the island would take more effort than anticipated. To further complicate matters, the Romans diffused their Sicilian efforts by making simultaneous attempts against other Carthaginian territories (Corsica and Sardinia). They met with some success, but the Roman state didn’t have the resources to affect a definitive outcome. Another incentive for switching to a maritime policy, was the devastating impact of Carthaginian privateers raiding the Italian coast and disrupting Italian trade. As a result, Rome decided to go onto the defensive in Sicily, mobilize her fleet, and invade the Carthaginian homeland in Africa.

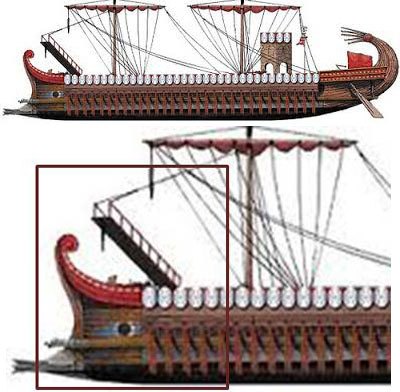

A Roman Quinquereme

This illustration is a side view of a quinquereme warship with corvus (highlighted in the second visual), a moveable plank with a beak at the end that when dropped onto an opposing enemy ship, holds it fast, allowing Roman marines to cross over to the opposing ship. The Corvus enabled the Romans to even the odds against the experienced seafaring Carthaginians.

Quinquereme Rower Arrangement (Cutaway Front View and External Diagonal View)

We have little concrete evidence of how quinqueremes arranged their rowers. The arrangement in this picture makes the most sense; 3 banks of oars, one rower manning the lower oar (shortest and lightest oar) while the second and third banks have two rowers to each oar. The picture below shows an external view of a quinquereme.

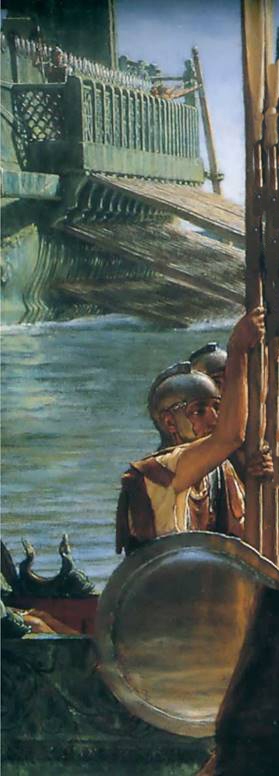

Roman War Galley

This picture is a detail from an Alma Tadema painting showing a Roman war galley (most likely a quinquereme). There are three banks of oars, presumably with one rower manning the lowest bank and two rowers to an oar in the two upper banks. Thus we have five rowers for every three oars. We think the word quinque (meaning five) relates to the number of rowers, while remus relates to oar. Polybius tells us that there were usually 300 rowers on a quinquereme (150 oars on each side) and the ship could hold from 70 to 120 marines, plus 20 sailors with on-deck duties. Thus each ship carried approximately 420 men. The number of Roman ships taking part in the battle numbered 330, making the number of participants 140,000. The Carthaginians had about 150,000. Needless to say, these are huge numbers.

The Sea Battle of Ecnomus–256 BC

To affect the invasion of Africa, the Romans prepared an enormous fleet of 330 ships, of which 250 were quinqueremes, and 80 horse transports. The fleet sailed from Messana, down along the eastern coast past Syracusa, to the port of Phintias, near Mt Ecnomus on the southern coast of Sicily where two legions were waiting to embark for the invasion of Africa.

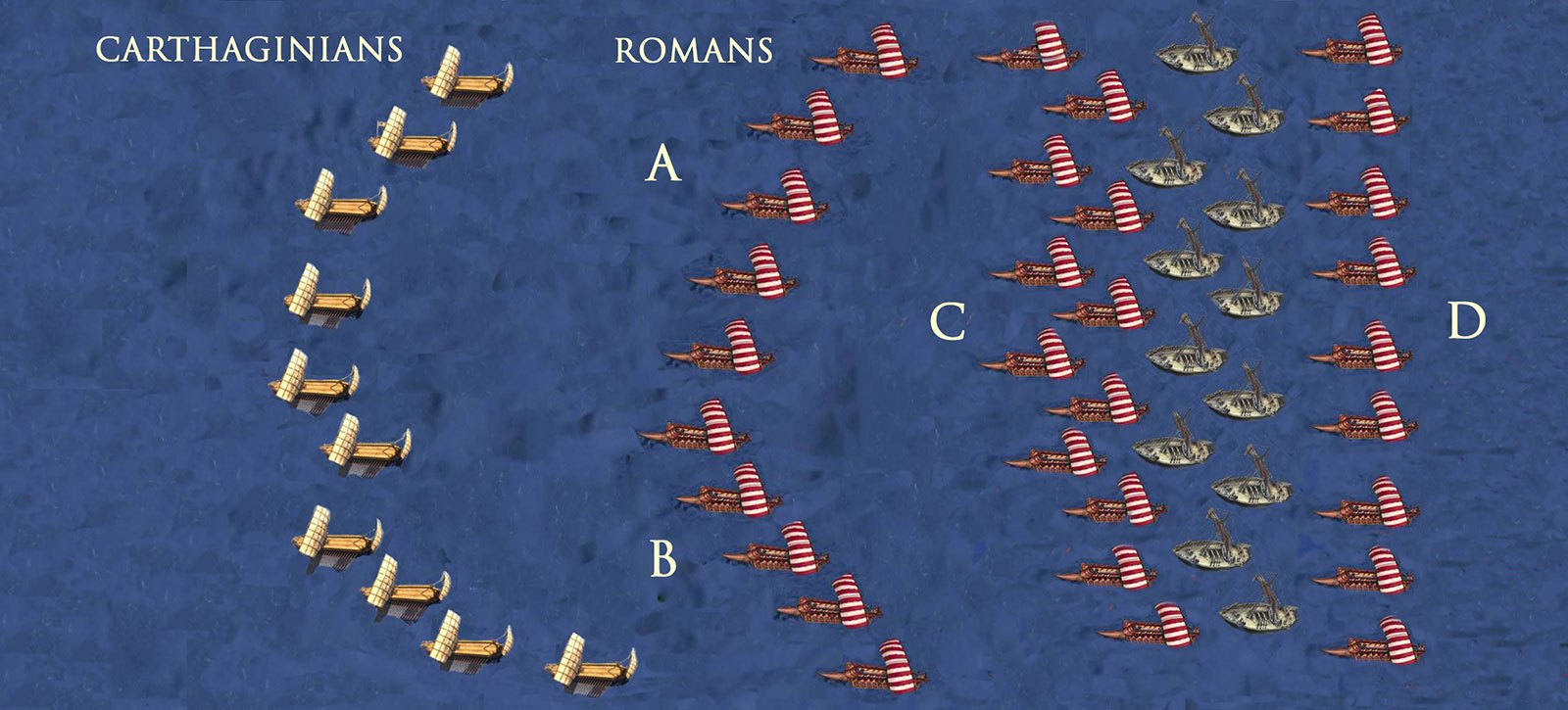

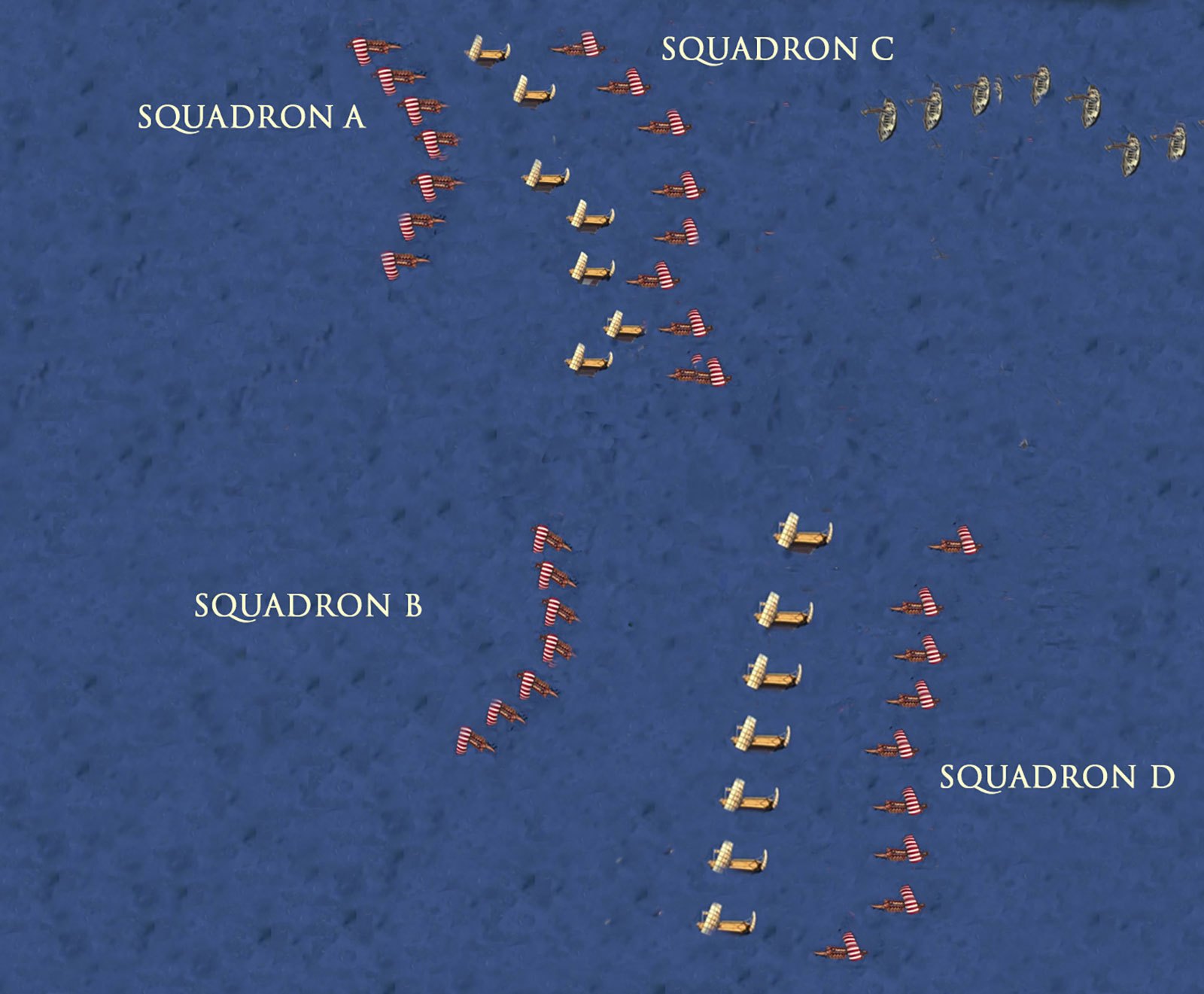

As the Roman fleet hugged the Sicilian coast, Squadrons A & B formed a wedge. Squadron C was towing empty horse transport ships. Squadron D covered the transports from the rear. The Carthaginian fleet approached to Romans in a convex crescent formation, the center the farthest away from the point of the Roman wedge.

Opening Phase of the Battle of Ecnomus: Carthaginians fleet approaches in a convex crescent while the Roman fleet is ordered in an triangle formation.

Battle of Ecnomus

The sea battle between the Carthaginian (left) and Roman (right) fleets was one of the largest naval engagements to take place in ancient times.

This battle diagram is based on a similar diagram found in Bagnall N. Essential Histories. The Punic Wars 264-146 BC. Osprey Publishing Ltd. London 2002, Page 42.

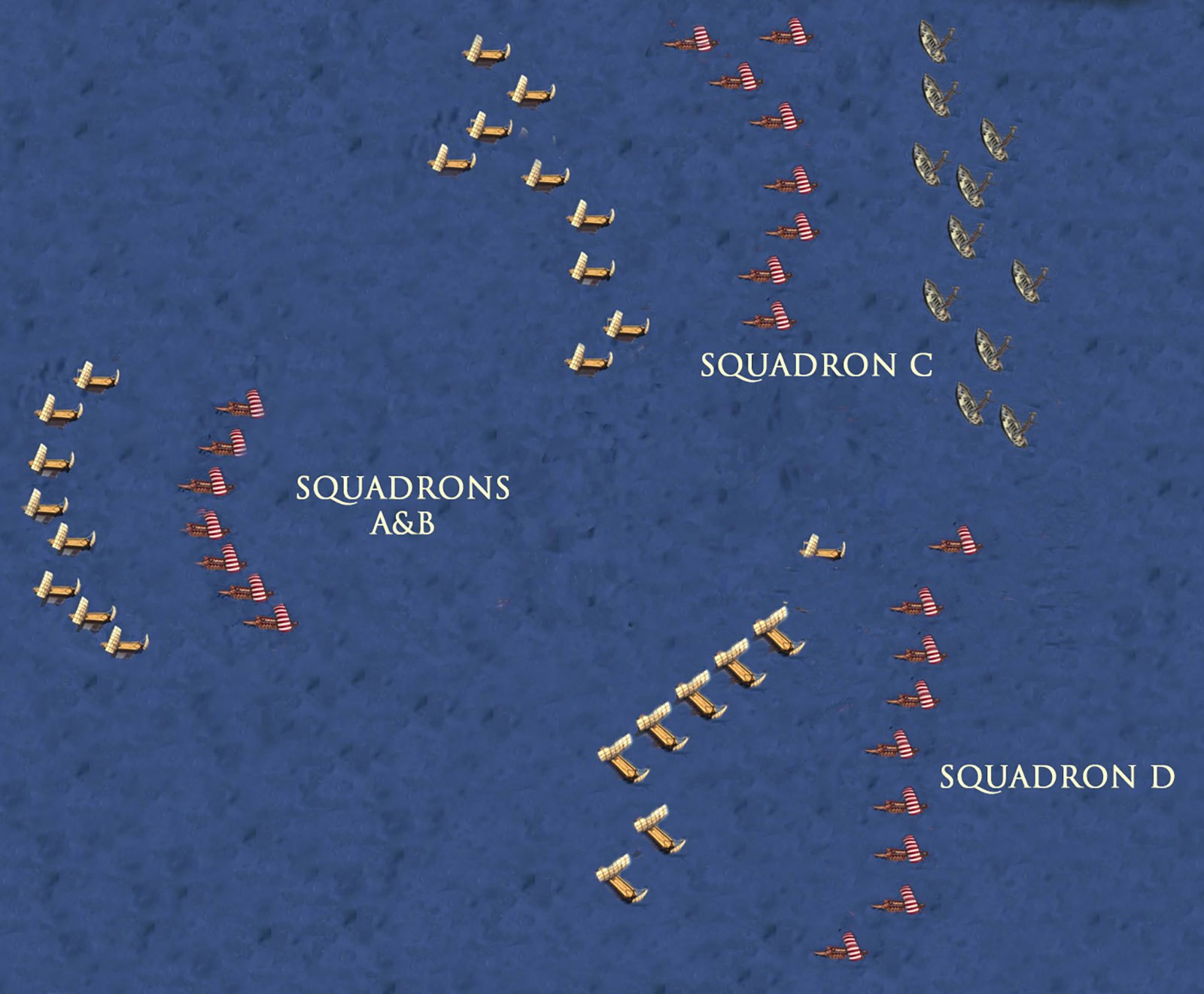

Second Phase of the Battle of Ecnomus

Roman squadrons A&B pursue retreating Carthaginian center which then does an about face and engages. Squadron C cuts loose the empty horse transports and makes a dash toward the Sicilian shore line. Squadron D engages the remaining Carthaginian squadron out at sea.

In contrast to the Roman fleet which was conceived as a sea battle fleet and an invasion flotilla, the Carthaginian fleet was equipped solely for a sea battle. It possessed faster ships and had no transports. Its purpose was to engage the Roman fleet and prevent a landing in Africa. The Carthaginians had about 250 warships divided into 4 squadrons. As the Roman fleet advanced, the two squadrons (A&B) that formed the wedge saw that the Carthaginian squadrons facing them were formed into a thin line and advanced aggressively to meet them. The Carthaginian squadrons facing the wedge turned and pretended to flee, drawing Roman squadrons A&B after them. This had the effect of breaking up the Roman formation. Meanwhile, the remaining Carthaginian squadrons attacked Roman squadrons C&D. Consequently, the engagement devolved into 4 separate battles.

As the fleeing Carthaginian squadrons drew Roman squadrons A&B out of formation, they did an about face and engaged them. This struggle did not go well for the Carthaginians and they began to flee in earnest. The victorious Roman squadrons then turned on the remaining two Carthaginian squadrons, overwhelmed and broke their formations.

Third Phase of the Battle of Ecnomus

Squadrons A&B defeat the Carthaginian Center then turn and attack the remaining Carthaginian Squadrons from behind.

In the end, the Romans lost 24 ships and the Carthaginians had 30 sunk and 64 captured. It was a devastating defeat for the Carthaginians and the way to Africa lay undefended.

The Roman maritime strategy was a success. By boldly committing to building a fleet and engaging the Carthaginians (an experienced maritime nation) on the sea, the Romans were able to regain the strategic initiative. The invention of the Corvus allowed to Romans to gain tactical superiority, to threaten Carthaginian cities in Sicily and to embark on an invasion of the Carthaginian homeland.