217 BC

Battle at Lake Trasumennus

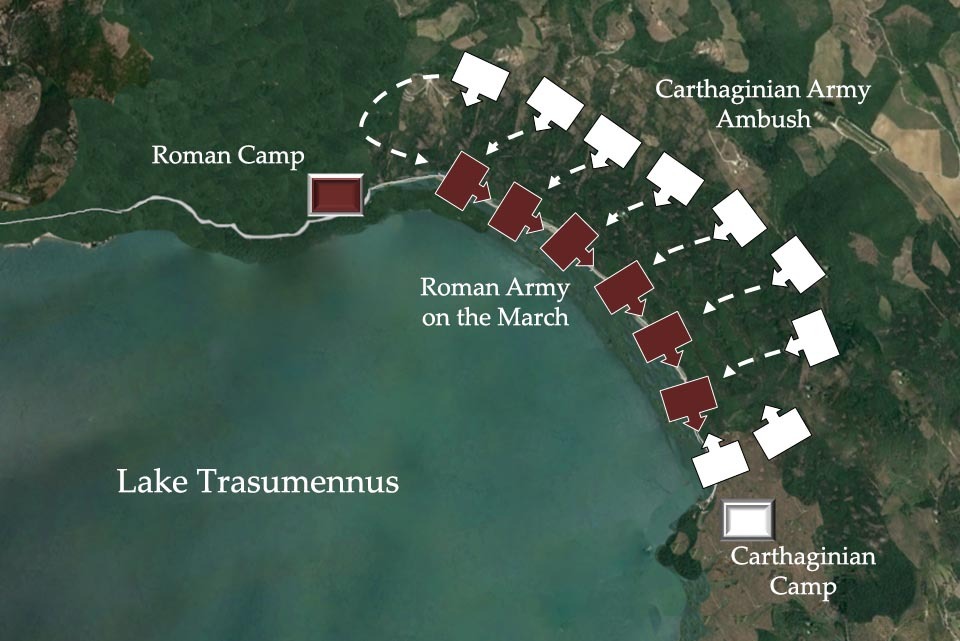

How the ambush of the Roman army may have occurred, by T.A. Dodge

The next morning, the Romans entered the valley which was largely covered in fog. As the army passed the defile, it spread out, in no particular order. After the last troops entered the valley, Hannibal sprang his trap. Dodge describes what probably happened next:

As the head of column reached the vicinity of the southerly exit, and began to halt to close up ranks, for they were now near where Flaminius had seen the Carthaginian camp, the Roman right was suddenly saluted with a loud blare of trumpets, the signal for a general attack by all parts of the ambushing Carthaginian line, which signal they again heard repeated and repeated along the hillside on their front and towards their left as far as the gap they had just filed through; and immediately thereupon they saw, advancing upon them through the rolling clouds of mist, the serried ranks of the Carthaginian phalanx. To add to the consternation of the moment, the thundering tread of charging horse, and the terrible shout of horsemen galloping to certain victory, came rushing down upon the head of column from the left.

Battle of Lake Trasumennus

Flaminius was one day’s march behind Hannibal. As his legions marched along the lake shore, they entered a narrow valley through an even narrower defile at the northern end. Once the entire army was in the valley, Hannibal sprang his trap.

The first idea of the Roman officers was that they had merely thrust their van into an ambuscade, and must at once withdraw it. The head of column was compromised. But they were soon undeceived. As far down the marching line as they could hear, for see they could not, the enemy’s light troops on the heights, with exulting shouts, debouched from

hiding, and rushing down the hills towards the carelessly spread-out Roman column, discharged their hail of leaden bullets and fired their darts and arrows upon the Romans, who were utterly unprepared for resistance and in nothing resembling order of battle; while from several of the heights, which in this plain came down close to the water, fell a constant rain of arrows and sling stones. Nor could the surprise and terror of the head of column exceed that of the rear, when, rushing from their wooded screen in the upper valley, the Numidians and Gallic horse and foot fell furiously upon the disordered troops.

It must be remembered that there was at that day no regular order of march in a Roman army, and Flaminius’ eagerness to get up with Hannibal had probably made speed rather than care the order of the day. There was no front, no flank, no rear. There was no way of retreat. On one side was the lake; on the other the hills from which debouched bodies of unseen but active foes; on right and left the attack of well-prepared and carefully arrayed battalions, instinct with the ardor of victory already won. Never was army worse compromised, never was army more certain of destruction. The Gauls had as yet had no chance to wreak their ill-will for many acts of cruelty done upon them by their Roman conquerors, and they now glutted their vengeance to the full. The Carthaginians saw that to-day they might wipe out the defeat and shame of the war in which their fathers had been so terribly punished, so deeply humiliated. The butchery was savage.

The Roman soldier, unconquerable when fighting within the lines of disciplined combat, appeared here to be no better than a brute beast led to the shambles. In the brief space of three hours, before the morning mists had lifted, there was no semblance of an army left, and still the butchery went on. Legions, Cohorts, Velites, Triari, all were mixed in one confused mass. Even the small bodies which hung together to defend themselves seemed incapable of wielding their arms; thousands threw themselves into the lake to seek a fate to them less cruel; other thousands put an end to their own existence. Livy states that so horrible was the tumult that neither party was aware of the occurrence of an earthquake, which at the very moment of the battle” overthrew large portions of many of the cities of Italy, turned rivers from their rapid course, carried the tides up into the rivers, and leveled mountains with an awful crash.” A body of six thousand men cut its way through towards Perusia, no doubt under cover of the fog. Not exceeding ten thousand men all told escaped this fatal day. Of the remaining thirty thousand, half were killed in their tracks, half captured. Hannibal’s loss did not exceed fifteen hundred men, mostly Gauls.

Hannibal at once sent Maharbal with the Spanish foot, some archers and the heavy cavalry in pursuit of the body which had escaped through the lines toward Perusia. They were surrounded next day on a hill they had occupied, and obliged to surrender to save their bare lives. On their surrendering, the Romans were made prisoners of war, the allied soldiers were all sent home without ransom.” I come not,” said Hannibal, “to place a yoke on Italy, but to free her from the yoke of Rome.” Some authorities have stated that of the whole force but six hundred cut their way through; that but nine hundred were captured; and that the rest, including Flaminius, were cut to pieces. Flaminius indeed fell with the rest. Well for him that he did! The first quoted figures are probably more nearly correct than the latter, which seem to go beyond probability. Certainly, however, Rome had never as yet seen so sad a day. Plutarch relates that Hannibal sought long for the body of Flaminius, to give it burial, but was unable to find it. The Roman soldier must not be underrated. The ten thousand legionaries of the centre at the Trebia cut their way through the Carthaginian army in good order, despite the utter demoralization of the rest of the army. The six thousand leading troops at Trasimene did the like. The Carthaginian was an older, not a better soldier. In material and basis of organization, and in the natural discipline and character of the race, the Romans were by far the stronger. The advantage of the Carthaginian soldier was the training which comes of long service and a strong leader; and the whole body profited by the expertness of its cavalry; but any superiority of the Carthaginians as an army lay solely in Hannibal’s genius.

Dodge, TA Hannibal A history of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. 3rd Edition. Originally Published by Houghton, Mifflin and Company. © 1891. The Riverside Press. Cambridge Mass. USA. Pages 303-314.